Executive Summary

Parents are more stressed than ever before, according to a recent Advisory by the U.S. Surgeon General.1 Yet the pressure of parenting does not fall equally on women and men. For families with children under 18 at home, the division of home responsibilities is grossly unequal. Mothers—whether they are married or single—do significantly more than fathers.

And it is not just among parents that women carry the load of essential work in the home. Across all groups, women are significantly more likely than men to spend more time on unpaid work in the home.

Gender Equity Policy Institute’s “The Free-Time Gender Gap” examines the gender disparities in time spent on unpaid childcare and household work, as well as the free-time gender gap which emerges alongside these imbalances. Analyzing data from the 2022 American Time Use Survey, we find that women consistently spend more time than men taking care of children and doing household work like cooking, laundry, and cleaning. We also uncover a free-time gender gap; women across almost every group studied have less free time than men to socialize, relax, and pursue their interests and hobbies.2

In fact, simply being a woman is linked to spending more time on unpaid childcare and household work and having less free time, even when controlling for age, income, race/ ethnicity, and marital status, as determined by multivariable regressions conducted by the Institute.3

Gender gaps in free time and time spent on childcare and household work are deeply rooted in longstanding cultural and social norms dictating women’s proper role in the home and family. Although shifts in America’s economy, culture, and belief systems have disrupted traditional gender norms and roles, the analysis presented here demonstrates that disparities in how men and women spend time remain pervasive. And there is no evidence that these gender gaps have narrowed in recent years.4 Policy change and cultural shifts both are necessary to rebalance these household responsibilities and advance gender equity in the United States.

Key Findings

Women spend twice as much time as men, on average, on childcare and household work. All groups experience a free-time gender gap, with women having 13% less free time than men, on average.

- Mothers spend 2.1X as much time as fathers on the essential and unpaid work of taking care of home and family

- Young women (18-24) experience one of the largest free-time gender gaps, having 20% less free time than men their age

- Working women spend 2X as many hours per week as working men on childcare and household work combined

- Married women without children spend 2.4X as much time as their male counterparts on household work

- Among Latinos, mothers spend 3.4X as much time as fathers taking care of children and doing household work

Women do significantly more childcare and household work than men, even when controlling for age, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, and other factors

From early adulthood through old age, women in the United States consistently spend more time than men doing household work and taking care of children, essential day-to-day responsibilities that are typically undervalued and unpaid.5

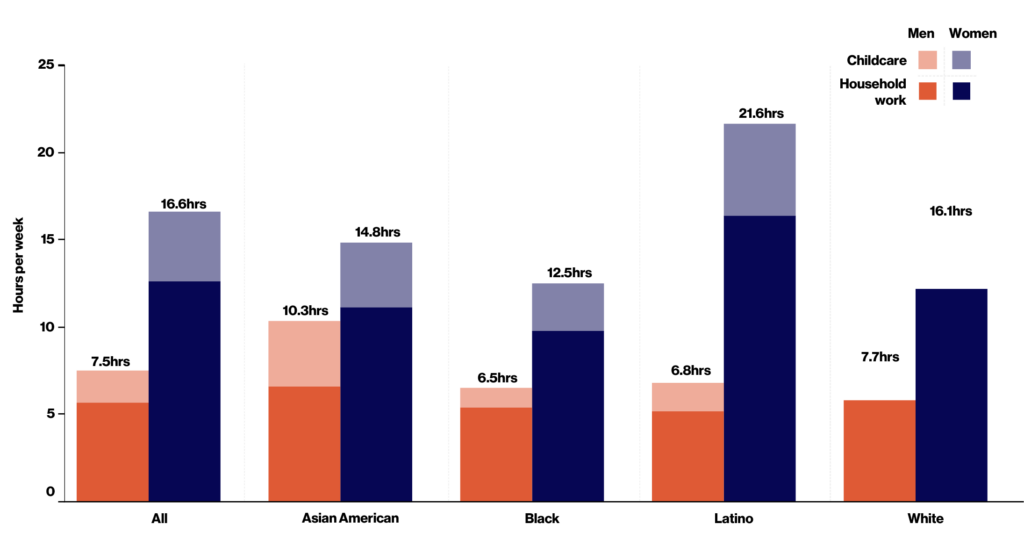

In an average week, women spend 12.6 hours cooking, cleaning, and doing other types of housework, while men spend 5.7 hours.6 Women also spend more than twice as much time as men taking care of children.7 Combined, women spend 2.2 times the amount of time as men doing household work and taking care of children.8

The unequal division of unpaid labor in the home begins as soon as women enter adulthood. Women 18 to 24 spend about twice the amount of time on household work as men their age. They do 8 hours of household work per week compared to just 3.8 hours for men.9

As people enter their mid-twenties, the prime working and childrearing years, the time women spend on combined household and family responsibilities noticeably increases. Among Americans 25 to 34, women do 2.3 times as much household work and 2.8 times as much childcare as men.10

As people reach their mid-thirties, a phase of life when many are married and have children, men take on a greater share of childcare and household work and the gap between women and men narrows slightly. Nevertheless, among those 35 to 44, women still do two times as much household work and 1.8 times as much childcare as men.11

Time spent on childcare tapers off as people reach their mid-forties, when children are typically older or already out of the home. Yet it is during this phase of life that gender disparities in household work surge.12

Among people 45 to 54, women do nearly two-and-a-half times as much cooking, cleaning, and other household work as men. Household work continues to be unevenly divided between senior women and men (65 to 74), with women doing twice as much household work as men.13

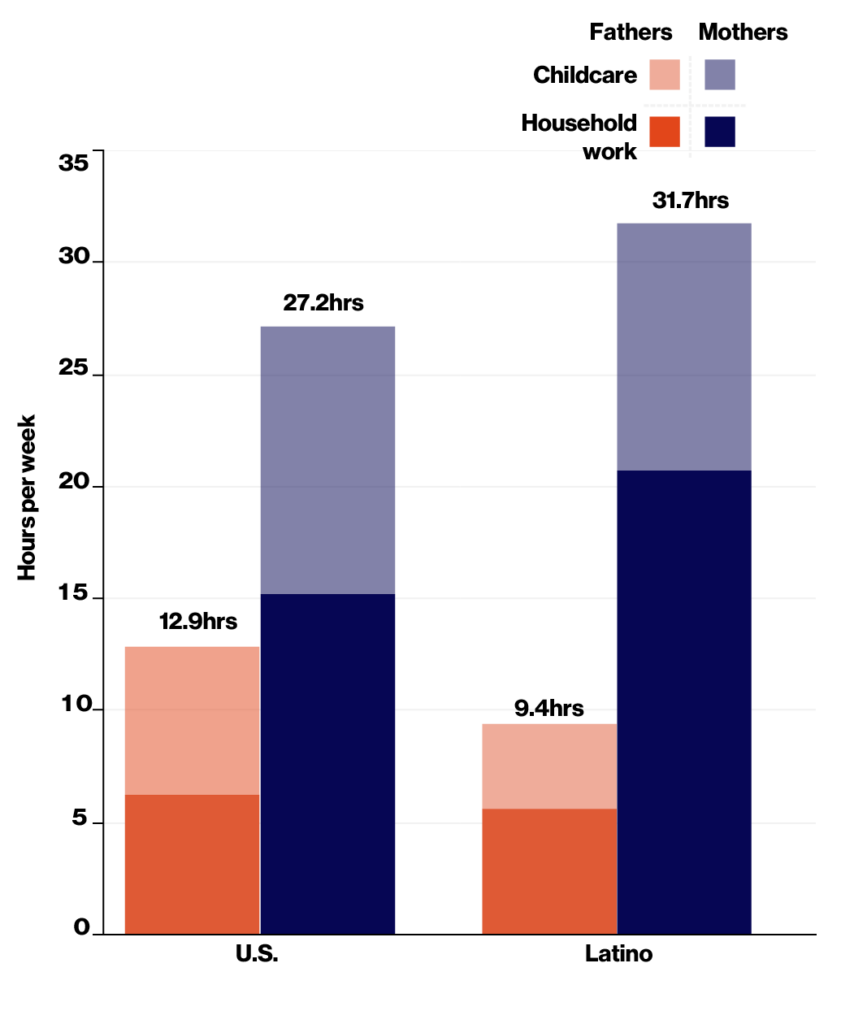

Figure 1: Weekly Hours Spent on Childcare and Household Work by Gender and Race/Ethnicity, 2022

Note: Labels represent weekly hours spent on combined childcare and household work, by gender and race/ethnicity. Estimates for certain race/ethnicity groups are not included due to small sample sizes. See appendix for a comprehensive description of the tasks included.

Source: Gender Equity Policy Institute Analysis of ATUS 2022.

Mothers spend nearly double the amount of time as fathers taking care of children and home

Raising children can be a great joy. For many parents, it can be tremendously fulfilling and give purpose to life. It is without question a social good, contributing to economic growth, civic life, community resilience, and national prosperity and security.

Unfortunately, American parents are under enormous strain. One-third report high levels of stress, according to a U.S. Surgeon General Advisory issued in August 2024, and time demands are one of the major stressors on parents. The report warns that the high level of stress parents experience is having a harmful effect on their mental health and well-being, as well as that of their children. It is noteworthy that Advisories are “reserved for significant public health challenges that require the nation’s immediate awareness and action.”

A supermajority of Americans (77%) believe that mothers and fathers should share the essential work of caring for children, keeping families fed and clothed, and maintaining clean and safe homes, according to recent public opinion polling. But the reality is starkly different, as Gender Equity Policy Institute’s analysis of time-use data reveals.

Women remain primarily responsible for taking care of children. Mothers, whether they are married or single, spend nearly double the amount of time on childcare as fathers do. They spend about 12 hours per week taking care of children compared to 6.7 hours for fathers. Likewise, mothers spend 2.4 times as much time as fathers on household work (15.2 hours per week versus 6.2 hours per week). Combining childcare and household work, mothers spend 2.1 times as much time as fathers on the essential and unpaid work of taking care of home and family.

While fathers do spend time caring for children through “secondary childcare”—that is, having a child under one’s care while focused on another primary activity—mothers still do more of this type of care.

Combining hours spent on “primary” and “secondary” childcare, mothers on average devote 47.6 hours per week to taking care of children. The time pressure on young mothers is particularly acute. Among parents 25 to 34, mothers spend 61 hours per week on primary and secondary childcare combined, while fathers spend 45 hours per week doing so.

Mothers with a high school education or less experience the largest gender disparity in childcare and household work, spending nearly triple the amount of time as their male counterparts (29.8 hours per week compared to only 10.3 hours per week). For women, having a high school education or less significantly increases how much time they spend on household work like cooking, cleaning, and shopping, as determined by GEPI’s multivariable regression analysis.

There are, likewise, substantial race/ethnicity differences among mothers themselves. Latina and White mothers spend the most time on childcare and household work, respectively 31.7 and 26.3 hours per week. Black mothers spend the least (19.7 hours per week) compared to mothers of other race/ethnicity groups.

Figure 2: Weekly Hours Spent on Childcare and Household Work by Gender Among all Parents and Latino Parents 2022

Note: Parents are defined as having at least one child under 18 in the household. Labels represent weekly hours spent on combined childcare and household work. See appendix for a comprehensive description of the tasks included.

Source: Gender Equity Policy Institute Analysis of ATUS 2022.

Within every race/ethnicity group studied, there is a gender gap, with mothers doing more childcare and household work than their male counterparts. The largest within group gender disparity is that among Latino parents, with mothers spending 3.4 times as much time as fathers on childcare and household work. The gender differences among other race/ethnicity groups are smaller, but still significant. White mothers spend twice as much time as White fathers on childcare and household work; Black mothers spend 1.6 times as much time as Black fathers.

The Unequal Burden of Household Work Affects All Women— Not Just Mothers

The unequal division of unpaid work in the home, such as cooking, cleaning, and shopping for food and clothing, is a powerful testament to the tenacity of old gender norms. Women do significantly more of this work than men do, even when there are no children living in the home. This holds true for women regardless of their marital status, their employment status, or their level of education.

Among all adults without children, women do twice as much household work as men, dedicating 11.7 hours per week to these tasks, on average, compared to 5.8 hours for men. Women in mid-life (45 to 54) without children at home spend an astounding 2.7 times as much time on household labor as their male counterparts.

Similarly, among all single people without children, women do nearly twice as much household work as men, spending 9.7 hours per week on household tasks compared to 5 hours for men.

Sharing a home with a spouse could, in theory, lighten the burden of housework for each person. But getting married seems to exacerbate the burden of household work on women. Married women do substantially more household work than their single women peers, while married men spend just a few minutes a day more than their single peers. Married women without children do 2.3 times as much household work as their male counterparts (14.4 hours per week versus 6.2 hours).

Working Women Struggle to Balance the Double Shift of Paid Work and Unpaid Responsibilities in the Home

Working women spend significantly more time than working men on unpaid work in the home. This is the case whether they work full-time or part-time. It is the case whether they have children or not.

Take household work like cooking, laundry, and the like. Women who work full-time do 1.8 times as much as men who work full-time; they spend 9.7 hours per week on it compared to 5.4 hours for men. Women who work part-time do 2.5 times as much household work as men who work part-time.

Even when there are no children in the home, working women do more unpaid household labor than their male peers. Among childless workers working full-time, women do 1.8 times as much household work as men. Among those working part-time, women do 2.4 times as much household work as men.

Having children, not surprisingly, increases the time pressures on working parents. Still, working mothers spend more time than working fathers on childcare and household work combined. Among parents working full-time, mothers do 1.6 times as much childcare and household work as fathers, spending 19.5 hours per week compared to 12.3 hours by fathers. Mothers who work part-time carry a far more unbalanced division of childcare and household work, doing 2.4 times as much as fathers who work part-time.

The Free-Time Gender Gap is Substantial

Women from all walks of life—whether young or old, single or married, highschool educated or holding advanced degrees—have significantly less free time than their male peers.

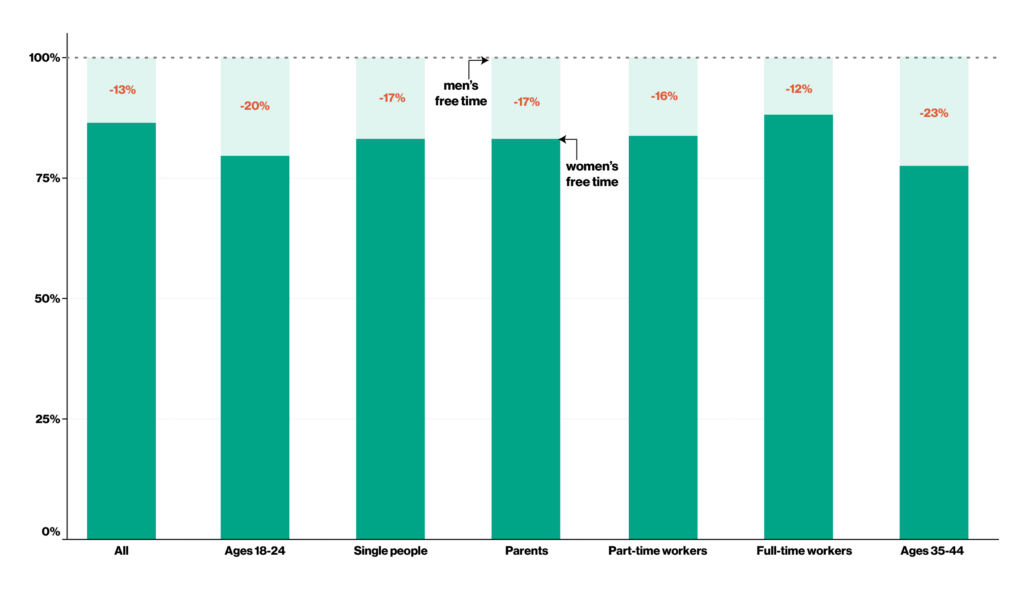

Across every group studied, men spend more time than women socializing, watching sports or playing video games, or doing similar activities to relax or have fun. Women overall have 13% less free time than men, on average. The gap balloons among some groups, with women having up to one-quarter less free time than men.

The free-time gender gap takes hold as soon as Americans become adults. Indeed, it is near its widest among people 18 to 24. Young women have 20% less free time than young men—and the gap is even bigger among young women and men without children. This free-time gender gap adds up quickly. Over the course of a week, young men have nearly 8 hours more free time than women; over the course of a month, men’s free time grows to 36 hours. In a year, an 18- to 24-year-old young man will enjoy, on average, nearly 434 hours more free time than a woman his age.

The free-time gender gap persists among single Americans. Single women overall have 17% less free time than single men. Being a single woman is associated with having around 2.6 hours less free time per week compared to a male peer, according to a multivariable regression analysis.

Parents naturally have less free time. Still, the free-time gender gap is comparatively large among them. On average, mothers have 17% less free time than fathers.

Women who work part-time have 16% less free time than their male counterparts, while women who work full-time have 12% less free time than men who work full-time. For full-time workers, it is as if men get a month more a year of vacation compared to their women peers.

The group with the least amount of free time is 35- to 44-year-old women. Men their age have a full hour per day more free time, and the free-time gender gap is near its peak at this time of life. Women 35 to 44 have 23% less free time than men their age.

The free-time gender gap in day-to-day life takes on even more significance when considering that the United States is the only advanced economy that does not guarantee paid vacation time to workers, and Americans work longer hours and take far less time off than those who live in other high-income countries. Americans are squeezed at work and at home, and the burden of these relentless time pressures falls disproportionately on women.

The Free-Time Gender Gap Affects All Women

Women overall have 13% less free time than men, on average. The gap balloons among some groups, with women having up to nearly one-quarter less free time than men.

Figure 3: Women’s free time as a share of men’s free time and the percentage penalty among selected groups. Parents are defined as having at least one child under 18 in the household. Labels represent the combined weekly hours spent on childcare and household work. See appendix for a comprehensive description of the tasks included.

Source: Gender Equity Policy Institute Analysis of ATUS 2022.

Conclusion

Gender inequality is both a cause and a consequence of the pervasive imbalance in the division of unpaid care and household labor in the United States. Traditional gender norms hold that a woman’s role is in the home taking care of children, while that of a man’s is to be the breadwinner and family protector. Although we hear echoes of this traditional view in current political and social media debates, the vast majority of adults in the United States hold more egalitarian views of gender roles.

But there is a wide gulf between our ideals and our realities, as we have seen in this report on how Americans divide the work of taking care of home and family. One reason for the persistence of these gender disparities is that the U.S. has failed to modernize its public policies to fit 21st century economic realities. Even though 78% of American women are in the labor force, the nation’s social infrastructure is still largely premised on the assumption that mothers will be at home with children.

Consider the work of raising children in the United States. Every high-income nation in the world provides for paid leave for new parents—except the United States. Most provide ample financial and institutional support for childcare and preschool. Our peers devote a substantial share of public spending to family benefits, but the U.S. invests only minimally in supporting families. For instance, family benefits account for 2.4% of GDP in Germany compared to 0.6% in the United States.

A year of childcare in many states in America costs as much as a year of college. In many communities, there are not enough spots in childcare for all parents who want or need it. Even when young children enter school, typical American school hours are grossly misaligned with the workday, forcing families to either spend money on after school care or reduce their work hours.

The lack of public support for child-rearing, in turn, compels families to make hard decisions about how to balance the family budget. It is often a rational economic decision for one parent to step away from paid work to care for children rather than pay for childcare. And because women tend to have lower earnings, they are more likely to be the one within a couple to make this trade-off between paid employment and caregiving.

Such understandable responses by families to America’s inadequate social infrastructure often further entrench gender inequality and its harmful effects on women. When women reduce their hours or leave the labor force to care for children, they lose out on valuable economic opportunities. The gender pay gap widens when women become mothers. Women who take time out of the labor force end up with lower Social Security retirement benefits. Women are more likely than men to be part-time workers; part-time workers typically earn less and are not eligible for employee benefits like health insurance and retirement. According to one analysis, by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, additional time spent on household and care work was associated with a decrease in women’s weekly earnings, when controlling for other factors. In other words, time inequality itself reinforces and perpetuates gender inequality.

Public policy alone will not entirely eliminate these deeply rooted gender disparities. Cultural change is needed too. But smart policy can nudge along positive behavioral change that ultimately advances equity and equality. For example, several countries include mechanisms in their family policy to encourage fathers to take paid parent leave. Many Nordic nations have a ‘use it or lose it’ provision for fathers. Other countries, like Canada, provide extra paid weeks of leave to families if both parents use the time. A host of benefits redound to everyone when fathers take leave and spend more time with their children. Many nations provide caregiving credits in their public pension systems, so that women’s retirement benefits keep pace with men’s.

The unequal division of care work, particularly, affects women’s opportunity and well-being in ways that cannot be measured solely in dollars and cents.

Take housing. Not only are women, particularly women of color and women-headed households, more likely to spend over half of their income on rent. But they also have less freedom in their choice of housing—because of their caregiving responsibilities. One way Americans deal with the housing affordability crisis is to move to distant suburbs and exurbs, where housing is cheaper than it is in central cities and job hubs. The tradeoff, however, is typically a long commute to and from work. But for women who are caring for children or elderly relatives, long commutes are often not feasible. Children and elderly parents get sick and need to get to doctors in the middle of a workday. School hours begin too late and end too early to accommodate a commute to a 9-to-5 job. Many mothers—whether married or single—often face a choice between keeping a full-time job or finding affordable housing.

Or consider how women and men experience climate change. Women’s disproportionate responsibility for caregiving also contributes to their greater vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. For example, when schools close due to climate-driven events, mothers might have to take unpaid time off of work or pay for childcare. As Americans experience more dangerous heat waves, wildfires, and floods driven by climate change, the caregiving demands on women can increase, as they are more likely to be the ones responsible for helping children and elderly adults stay out of harm’s way.

Finally, as noted above, the stress of parenting in America has become a public health crisis, according to the U.S. Surgeon General. Parents are working longer hours and devoting a record amount of time to taking care of children. Physically and emotionally demanding, these responsibilities chip away at the time that parents have left over for rest, fun, and fostering personal relationships. The mental health and well-being of both parents and children are at risk from the pressures on today’s parents. Yet the Advisory stops short of acknowledging the unequal division of labor between women and men. Rather, it underplays the harsh reality that the stress of parenting falls disproportionately on mothers, who are left particularly vulnerable to burnout and mental health problems.

Confronting the stubborn gendered disparities on unpaid care and household work is critical to advancing women’s equality in the United States.

The fact that women from all walks of life have significantly less free time than men—and spend significantly more time on household work—is a sign that outdated gender norms still exert a powerful influence over our lives.

Our hope with this report is that making these gender gaps in how Americans spend time visible can contribute to a broader public conversation about what it will take to reach a more balanced, fair, and equal division of care and household labor.

After all, time is a finite resource. How we get to spend our limited time could not be more essential to personal well-being and happiness and the flourishing of American families and communities.

Appendix and Methodology

For Appendix and Methodology for this report, please download the pdf.

Citation

Natalia Vega Varela, and Leyly Moridi “The Free-Time Gender Gap: How Unpaid Care and Household Labor Reinforces Women’s Inequality,” Gender Equity Policy Institute, October 2024. https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.13759857

Contact

For media inquiries, email: [email protected] | [email protected]

To reach the authors, email: [email protected]

Statement of Research Independence

Gender Equity Policy Institute is a nonpartisan 501c3 organization. The Institute conducts independent, empirical, objective research that is guided by best practices in social science research. The Institute solicits and accepts funding only for activities that are consistent with our mission. No funder shall determine research findings, conclusions, or recommendations made by the Institute. Gender Equity Policy Institute retains rights in intellectual property produced during and after the funding period. We provide funders with reproduction and distribution rights for reports they have funded. Gender Equity Policy Institute is solely responsible for the content of this report.