Key Findings

- California has the lowest maternal mortality rate among states publicly reporting

- California mothers were 5x as likely to survive pregnancy and childbirth as mothers living in states that banned abortion after Dobbs

- California teens are half as likely as teens in banned states to become mothers

- Women in California are half as likely to lack health insurance as women living in banned states

- Latina women in California are more likely to give birth during their teen years and are less likely to have health insurance, compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the state

Executive Summary

One year after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned the Constitutional right to abortion enshrined in Roe v. Wade, women in the United States face numerous complex challenges in accessing reproductive healthcare, particularly in states that banned abortion after the decision.1

This study reports on the state of reproductive and sexual health in California during the final years of the Roe era. Building on Gender Equity Policy Institute’s The State of Reproductive Health in the United States (January 2023), we analyze data on key reproductive health indicators—maternal mortality, teen births, and newborn deaths—and compare outcomes and trends between states grouped by reproductive healthcare access.2 Our objective in this state focused report is to establish a baseline on women’s reproductive and sexual health in California relative to the nation and other states.3

California has excellent outcomes on measures across the entire continuum of women’s reproductive health and well-being, on which abortion care is one—albeit important—aspect. Among states publicly reporting data, California has the lowest maternal mortality rate in the U.S., less than half that even of the states that are supportive of reproductive freedom.4 By comparison, the maternal mortality rate in states that banned abortion in 2022 after Dobbs is nearly 5 times as high. On every indicator, women, pregnant people, and their babies have healthier outcomes in California and the other supportive states than they do in banned states.

California has been a leader in advancing women’s sexual and reproductive health for decades. After Dobbs, policymakers responded swiftly and decisively to put in place some of the nation’s strongest measures to protect reproductive freedom and prepare for the impact on California of abortion bans in other states. Voters overwhelmingly passed an amendment to the state Constitution to enshrine the right to abortion and contraception. More than 40 organizations, including sexual and reproductive health care providers, advocacy organizations, and legal and policy experts established the California Future of Abortion Council to coordinate reproductive freedom and justice efforts. Since its formation, the council has issued policy recommendations “to strengthen legal protections for consumers and abortion providers, expand the reproductive health care workforce, and ensure access to affordable care for low-income residents and communities of color.” Many of these recommendations were enacted into law in 2022 and others are pending in 2023.5

The trends in California on health outcomes are largely positive. Nevertheless, California can do better. Compared to other supportive states, California ranks best only on maternal mortality; on other indicators, California ranks between 5th best and a middling 13th. Racial and ethnic disparities, common throughout the U.S. in all three groups of states (supportive, restrictive, and banned), are narrowing in California. But they remain unacceptably high.

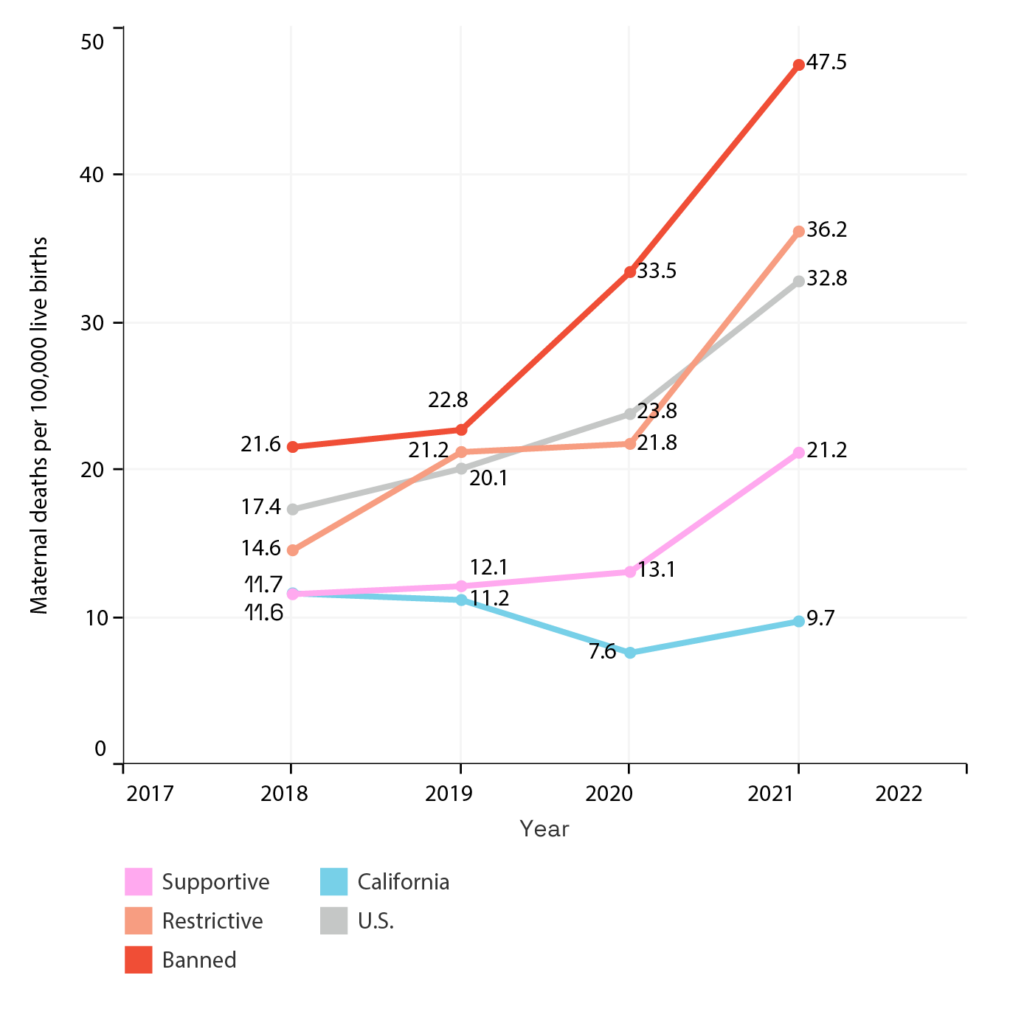

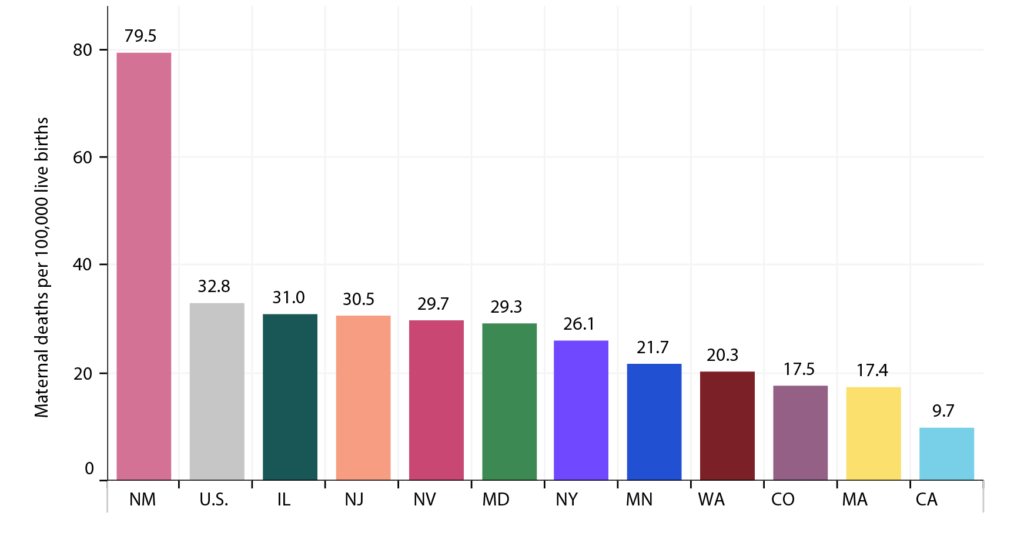

Maternal Mortality

The available data suggests that mothers in California are among the most likely in the nation to survive pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Between 2006 and 2013, California cut its maternal mortality rate in half, largely through efforts by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. In 2021, the state recorded 9.7 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, a third less than the U.S. average of 32.8. It is notable that among states reporting data, California’s maternal mortality rate is the lowest.6

California’s success in reducing maternal mortality is even more dramatic when compared to states that banned abortion in 2022. In those banned states, the maternal mortality rate was almost 5 times as high as the rate in California (47.5 per 100,000 live births).

There are significant racial and ethnic disparities in U.S. maternal mortality rates. In the nation overall, Black and Native American mothers have a greater likelihood of dying during pregnancy, childbirth, and the post-partum period than those in other racial/ethnic groups. Asian American and Pacific Islander (API) mothers are the least likely to die. Unfortunately, the data for California is insufficient to report on the maternal mortality rate of these three groups.

Maternal Mortality Rate, By State Abortion Access

Graph shows maternal deaths for 100,000 live births for U.S. and state groups. Maternal death is defined as a death during pregnancy or within 42 days after pregnancy due to any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management, not including accidental/incidental causes. Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2018-2021).

Maternal Mortality Rate, States Supportive of Abortion Access

Graph shows maternal deaths for 100,000 live births for U.S. and state groups. Maternal death is defined as a death during pregnancy or within 42 days after pregnancy due to any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management, not including accidental/incidental causes. Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2018-2021)

For California Latinas, who make up roughly 4 in 10 California women, the data on maternal mortality shows largely positive outcomes—especially compared to recent trends in other states. The maternal mortality rate for Latinas in the U.S. has, historically, been relatively low.7 But nationally, it rose steeply during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Much of the excess maternal mortality in both 2020 and 2021, according to a report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, was due to deaths from COVID-19. Pregnant and post-partum women were more susceptible to COVID infection and more likely to have severe symptoms.8) In Texas, the first state to effectively ban abortion, the maternal mortality rate for Latinas tripled between 2018 and 2021, reaching 44.5 per 100,000 live births. In California, however, the Latina maternal mortality rate during the pandemic increased only marginally, from 8.4 to 9.6 per 100,000 live births.

Maternal Mortality Rate, Latinas, Comparison of California, Texas, US

Maternal death is defined as a death during or within 42 days after pregnancy due to any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management, not including accidental/incidental causes. Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2018 – 2021).

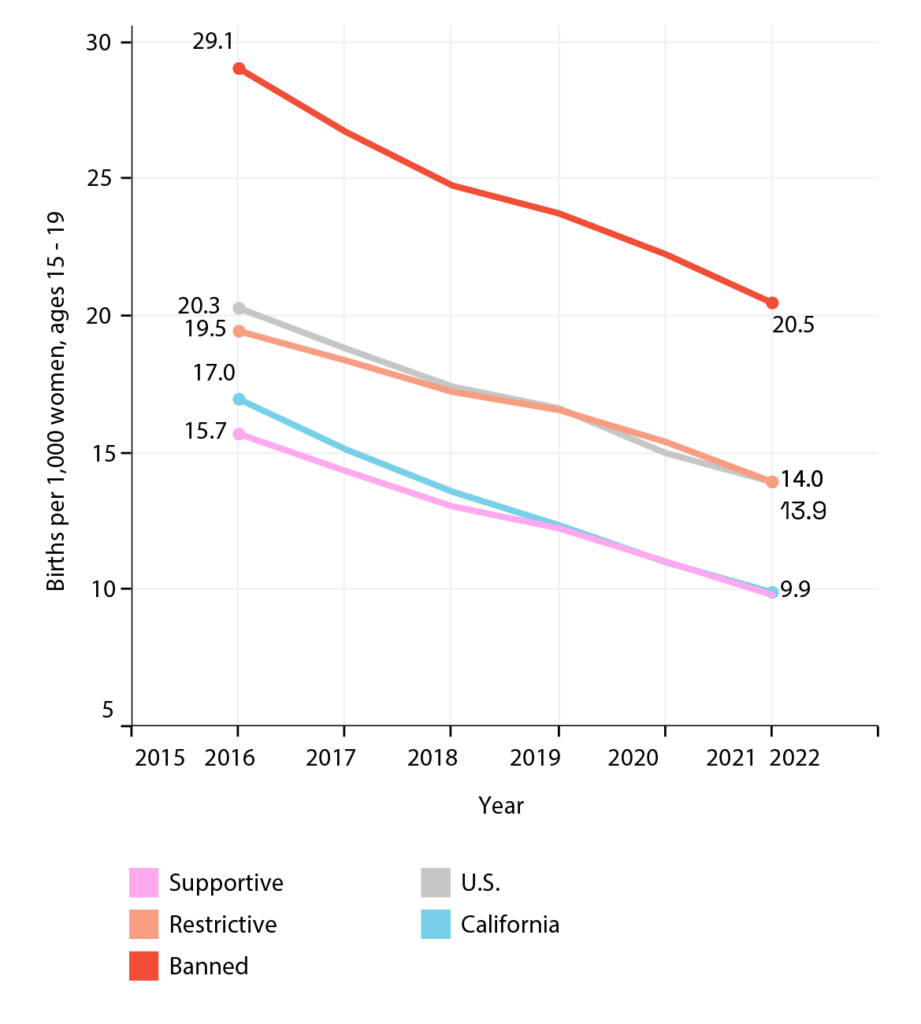

Teen births

The teen birth rate in California is substantially lower than the U.S. overall and roughly the same as that of supportive states. In California, it is less than half that of banned states.

The teen birth rate declined significantly across the U.S. in the Roe era. Since 2016, this trend has continued, with California having one of the most substantial declines among all states.

Teen Birth Rate, By State Abortion Access

Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2015-2021).

California has made particularly strong progress in reducing rates as well as in narrowing racial/ethnic gaps in the teen birth rate, although more improvement is needed. The highest rates of teen births nationally are found among Latina, Black, and Native American adolescents. (There is insufficient data on Native American teens.) In California, API teens have the lowest birth rate, while Latina teens have the highest. Black teens have a somewhat lower birth rate than Latinas. Still, teen births among both Latina and Black teens have dropped dramatically in California since 2016. Among Latinas, it declined by nearly 50%.9

California Latina adolescents are substantially less likely to give birth as teens than their counterparts in other states. Compared to Latinas in banned states, California Latinas are about half as likely to give birth during their teen years (14.1 compared to 27.4). And compared to those in other supportive states, California Latinas are the least likely to give birth as teens.

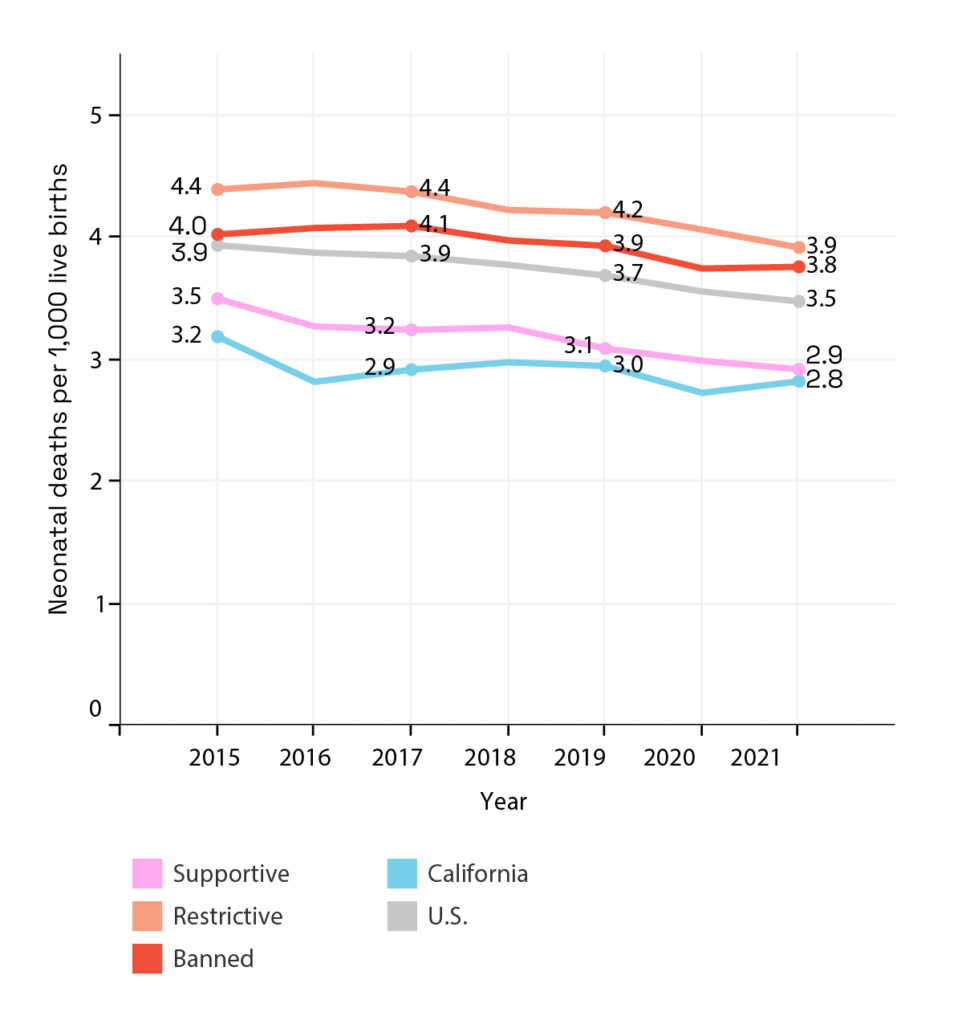

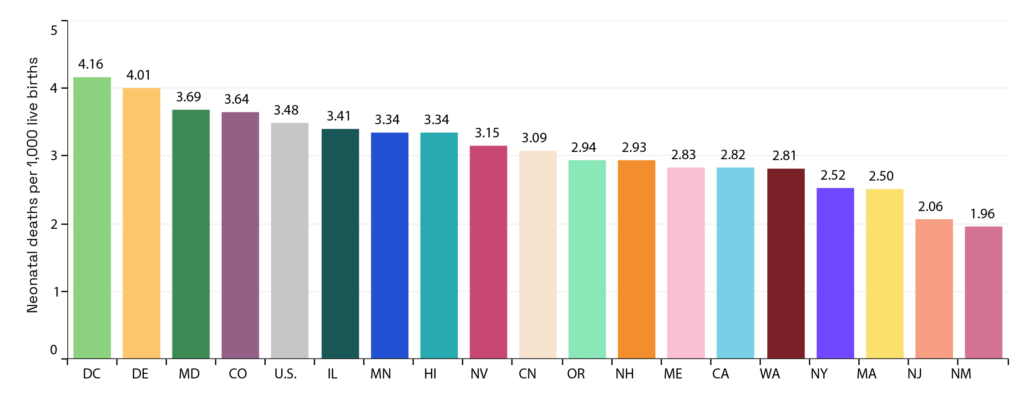

Neonatal Mortality

The neonatal mortality rate in California in 2021 was 2.8 deaths per 1,000 live births, below the national average of 3.5. California is among the top ten best performing states overall.

But throughout the nation in all three state groupings (supportive, restrictive, and banned), racial disparities are particularly stark. In the U.S. overall, Black babies are significantly more likely to die in their first thirty days of life. Research has shown that systemic racism and implicit racial bias are factors in these racial disparities.10 These racial inequities are most severe in restrictive states.

Neonatal Mortality Rate, By State Abortion Access

Newborn death is defined as a death in the first 30 days of life. Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2015-2020).

Neonatal Mortality Rate, States Supportive of Abortion Access

Newborn death is defined as a death in the first 30 days of life. Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of CDC (2015-2020).

Among all states, California ranks 6th for the survival of Latino babies and 15th for the survival of Black babies. Moreover, the neonatal mortality rate for Black babies is disturbingly high compared to that for other groups. It is two times as high as that for California babies overall (6.09 compared to 2.92).11

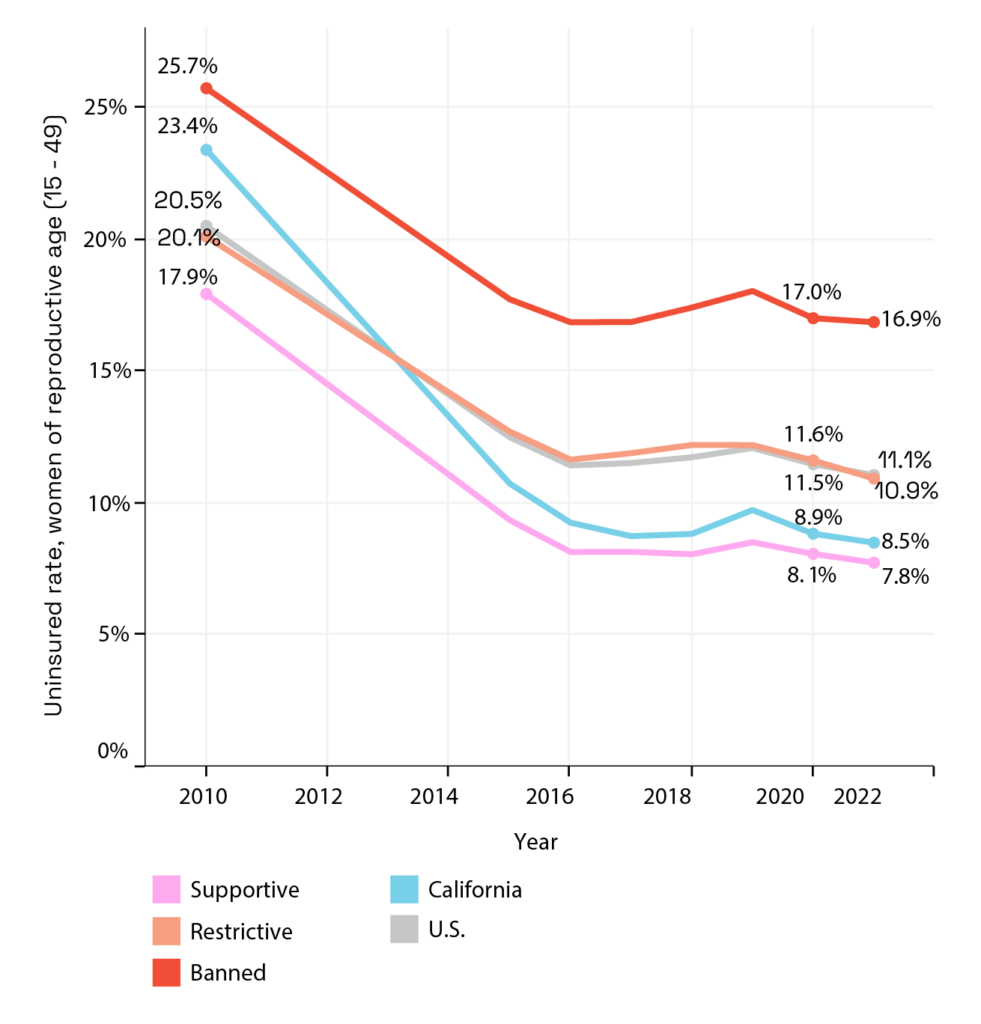

Health Insurance Coverage

Women of reproductive age in California are half as likely to lack health insurance as those living in banned states. In California, 8.5% lack health insurance, below the U.S. average of 11%. Yet California fares much worse than other supportive states on insurance coverage, ranking in the bottom half of these 22 states.

Women of Reproductive Age Without Health Insurance (%), By State Abortion Access

Gender Equity Policy Institute analysis of ACS (2010-2021).

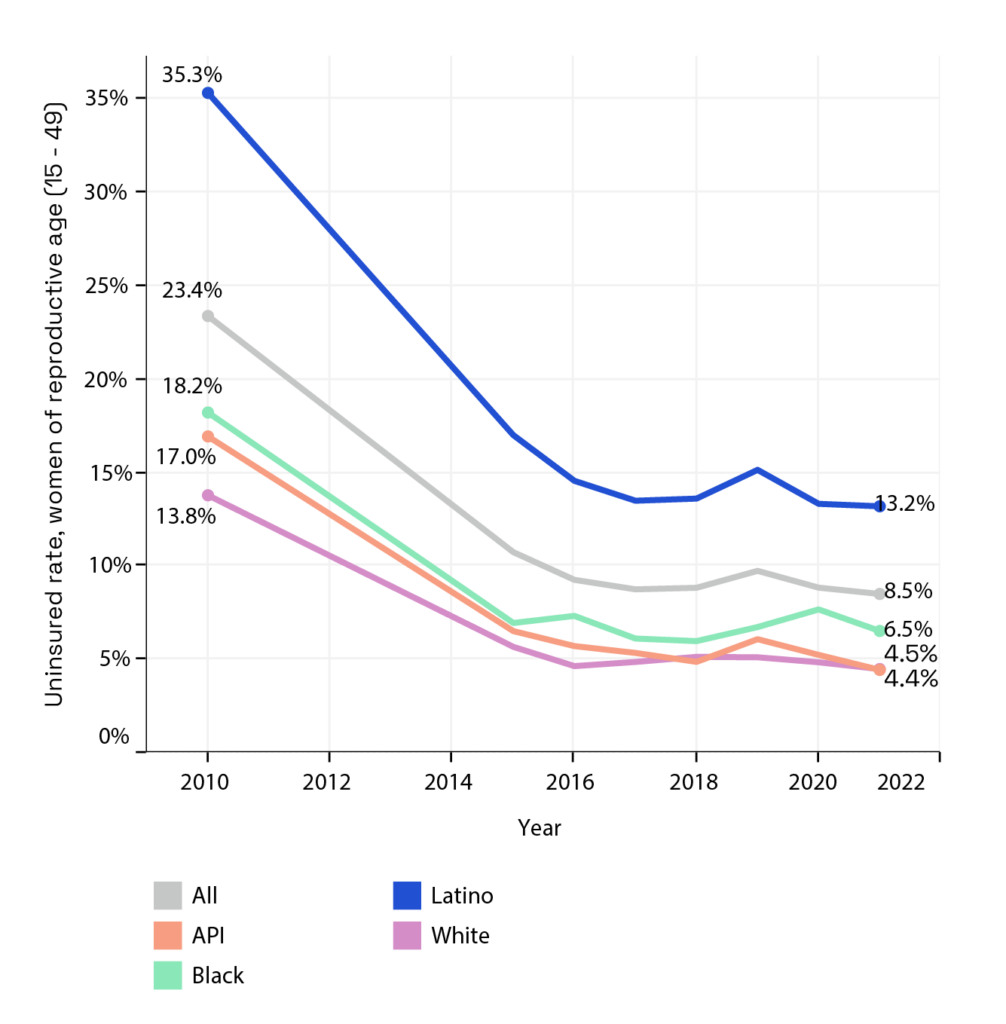

Latinas are particularly at risk of being uninsured, a reflection most likely of the large numbers of undocumented people among the Latino population.12

Women of Reproductive Age Without Health Insurance (%), By Race/Ethnicity, in California

The rate of insurance coverage for women of reproductive age, however, is an imperfect indicator of whether a pregnant person and their baby has access to healthcare during pregnancy and the postpartum period. With 33 other states and Washington, D.C., California makes Medi-Cal available to all eligible pregnant people—including undocumented immigrants—for up to 12 months after childbirth.13

Conclusion

On every indicator, pregnant people, women, and their children have healthier outcomes in California and the other states that are supportive of reproductive freedom. Likewise, the trends in these states are largely positive.14 In contrast, on every indicator, those who live in states that ban abortion or restrict reproductive and sexual health services have poorer outcomes. They face grave risks to their own and their babies’ health and well-being during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

In California specifically, we see clear improvement in reproductive health and well-being for women and their babies. The state’s success underscores the divergence between states.

Comparing states and examining data for the years 2015 through 2021—the last full year of data before the right to abortion was taken away by the Supreme Court, we see a clear and disturbing pattern. For people in their reproductive years and their babies, two Americas exist—one in which they can control when and whether to have children, and another in which they cannot—with dramatically different results for health and well-being. It is important to underscore that this was already the reality before Dobbs. As states continue to pass and enforce abortion bans, the divergence between supportive states and restrictive and banned states can be expected to widen. Historically marginalized people will be the most likely to suffer harm.

California, given the largely positive outcomes and trends on key reproductive health indicators reported here, can serve as a model for other states. Following California’s lead, they can enact laws to protect abortion care and contraceptive access, reduce costs for patients, and put in place legal protections for providers. States or advocates can move Constitutional amendments, through referendums or legislative action, to establish the right to abortion and contraception. Advocates and healthcare providers can join together in bodies like the California Future of Abortion Council to provide state-specific policy recommendations. To ensure women have comprehensive care along the full continuum of their reproductive years, states can fully cover contraceptives with no cost sharing.

At the same time, as California’s policymakers work to enhance protections of reproductive rights and healthcare access, they must dedicate effort and resources to reducing racial and ethnic disparities. They must also strive to improve outcomes overall, in order to match the performance of the handful of states that do better than California on teen births and neonatal mortality.

The post-Dobbs legal landscape has increased the urgency for states supportive of reproductive freedom to act independently to improve access to healthcare and protect women’s rights. California’s record offers some reassurance that individual states have the power and capacity to protect the health and well-being of women, gender diverse people, and babies in post-Dobbs America.

Citation

Natalia Vega Varela, Nancy L. Cohen, Shanoor Seervai, “The State of Reproductive Health in California,” Gender Equity Policy Institute, June 22, 2023. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8066808

Contact

For media inquiries, email: [email protected]

To reach the authors, email: [email protected]

Statement of Research Independence

Gender Equity Policy Institute is a nonpartisan 501c3 organization. The Institute conducts independent, empirical, objective research that is guided by best practices in social science research. The Institute solicits and accepts funding only for activities that are consistent with our mission. No funder shall determine research findings, conclusions, or recommendations made by the Institute. Gender Equity Policy Institute retains rights in intellectual property produced during and after the funding period. We provide funders with reproduction and distribution rights for reports they have funded. Gender Equity Policy Institute is solely responsible for the content of this report.